Blastomycosis—What Every Dog Owner Needs to Know

My mission is to help you have a healthier dog and breeders to raise healthier Llewellin Setters puppies through educational content based on over twenty years raising, training, and breeding Llewellin Setters. To help support these efforts, this page may contain affiliate links. I may earn a small commission for qualifying purchases at no cost to you.

Blastomycosis, or Blasto as it is often called, is a very serious and potentially deadly, systemic fungal disease that can affect dogs, humans, and other mammals. Blasto is caused by inhaling the spores of the fungus Blastomyces dermatitidis. B. dermatitis grows as a mold in acidic, organically rich sandy soils, decaying wood and other vegetation; and near bodies of fresh water with fluctuating levels such as streams, creeks, beaver lodges, and lakes.

When the soil or vegetation where the fungus lives is disturbed, the spores are released into the air and either inhaled where it then travels to the lungs, or it can enter the body through a puncture wound. After the organism multiples, it can travel from the lungs or wound to the vascular system or lymph nodes.

The soil can be disturbed by simply digging in the dirt, following a scent trail, or in dry weather the spores simply spread through dust in recently excavated areas, farmers plowing fields, areas undergoing construction, etc. It is generally found in the soil near fluctuating waterways and the right conditions—being temperature and humidity—must be present at just the right time to produce the spores, thus, it is very difficult, if not impossible, to isolate the source.

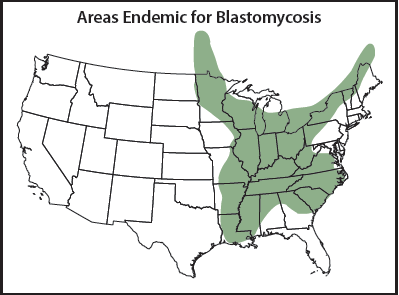

Nationally, Blastomyces dermatitidis has a wide distribution in North America.

- Endemic Areas, US – Mississippi, Missouri, Ohio River valleys, Eastern Seaboard, areas adjacent to the Great Lakes. States with highest endemicity are Wisconsin, Minnesota, Missouri, Illinois, Michigan, Kentucky, West Virginia, Arkansas, Tennessee, North Carolina, South Carolina, Louisiana, and Mississippi. Other endemic states include Indiana, Iowa, Ohio, Virginia, Georgia, and Alabama. However, cases do occur outside the endemic areas.

- Endemic Areas, Canada – Blasto is prevalent in Kenora, Ontario. Also found in Manitoba, Ontario (Kenora, Sault Ste. Marie, Chapleau), Quebec, New Brunswick, in particular areas around the Great Lakes and in a small area a small area in New York and Canada along the St. Lawrence River. Has also been increasingly reported along the Georgian Bay coastline (including Midland and Penetang), Dryden, and in Southern Ontario at the Rockwood Conservation area.

Dogs at the greatest risk for developing blastomycosis are 2- to 4-year-old intact male dogs living in endemic regions. Sporting dogs and hound breeds are most likely predisposed due to running and sniffing in high-risk areas during hunting. However, all breeds and ages are susceptible and the fungi can occur in any rural and urban environment. Residence near a river or lake and access to recently excavated sites has demonstrated an increased risk of infection. Blasto is not communicable from dog to dog, or dog to human. It is advisable however, that if a human has an open sore to wear gloves while handling the excrement, saliva, tissues, etc., of an infected animal.

The time between exposure to Blastomyces dermatitdis and infection varies from weeks to several months with most cases being reported in late summer to early fall. The Minnesota Department of Health reports the median incubation period is 45 days (range, 21 to 106 days). Dogs are usually sick for several weeks before the diagnosis is made and is usually mistaken for other illnesses. During the course of the disease the symptoms may improve slightly only to worsen again.

At normal canine body temperature, the organism transforms to yeast that can infect the lungs and spread systemically. Infection almost always begins in the lungs before traveling to other body tissues. The most common sites of apparent infection include the lungs, lymph nodes, eyes, skin, and bone.

Diagnosis of Blastomycosis can be difficult and is commonly mistaken for cancer, pneumonia, and even allergies because it is rare in most areas and your veterinarian may not be familiar with Blasto. If misdiagnosed and treated as a bacterial infection with antibiotics or as an allergy (because of breathing problems or a small sore that might be associated as a hot spot) with steroids, this will likely aggravate the situation. You must be persistent with your veterinarian.

And you must know the warning signs, which can include:

- Dry, persistent cough (Lung pathology occurs in 65-85% of cases)

- Loss of appetite/weight loss

- Vomiting

- Difficulty breathing

- Lethargy, exercise intolerance

- Depression

- Fever (a temperature >103°F is present in 40-60% of infected dogs)

- Skin sores that will not heal (30-50% of infected dogs). Skin lesions most commonly involve the nose, face, and nail beds.

- Limping (Bone infections causing lameness occur in 30% of dogs)

- Swollen lymph nodes (occurs in 30-50% of infected dogs).

- Eye infection, sudden blindness (Ocular lesions are identified in 20-50% of cases)

- Twitches, stumbling while walking, loss of coordination/balance.

- Less commonly infected include the prostate, testes, kidneys, joints, and brain. Central nervous system infections are identified in only 3-6% of cases and neurologic findings include depression, lethargy, neck pain, and circling.

Diagnosis is usually via an x-ray of the lungs and will look like they are full of cotton (snowstorm pattern). Blood, urine, tissue, and biopsy samples also aid in diagnosis and should be insisted on in the event a chest x-ray does not show the usual signs and if your dog has been in an environment of dirt-moving activity, recent construction, hunting, etc., within the past six–twelve weeks.

Blasto is treatable as long as the diagnosis is made early. Treatment usually lasts several months and the costs can run thousands of dollars. The key is early detection. The current preferred choice of treatment is the antifungal medication itraconazole. It is well tolerated by most dogs and has relatively few side effects in comparison to the drugs used previously. Others have reported success using fluconazole. In severe, life-threatening cases, Amphotericin B can be the preferred treatment, but can present serious side effects because of its toxicity to the kidneys.

At the beginning of treatment, many dogs condition can worsen for the first 5-8 days due to the dying-off effect of the yeast organisms.

Relapse can occur and is more common when the infection involves the nervous system, testicles, and eyes. Dogs may need to be neutered to remove the potential source and if ocular infection is present one or both eyes may be removed, especially if it has already been blinded.

There is no vaccine for Blastomycosis. The fungus is often very isolated and difficult, if not impossible, to source. There is no reliable means of detecting it in the soil, therefore no way for it to be eliminated from the soil. The spores are only briefly present in specific conditions.

Knowing if Blastomycosis has occurred in an area, recognizing the symptoms, and early diagnosis are the best defenses in prevention. We can’t stop hunting, but we can be aware of our surroundings. I would suggest not allowing a dog to actually play, dig, or forage in areas of rotting vegetation around edges of water (in areas where water levels can fluctuate or flood, it is thought this can be up to a mile away), dense, dark wooded areas, and excavation sites with loose dirt.

Our Blasto Story

Some of you may have heard that we lost our Luke dog on July 11th, 2012. At the time of his death the reason was unknown. Even after the autopsy, the reason was unknown but it looked like prostate cancer. Tissue samples were collected and sent for analysis. Luke had Blastomycosis. Luke never presented with the “usual” symptoms of Blasto. He never had a cough; he had no skin lesions or sores, and his lungs were clear. His first symptom was decreased appetite, which was attributed to 100°F and several bitches in heat. He also acted depressed, which was attributed to him being moved to another building away from his harem! I noticed him straining to eliminate himself, revealing enlarged testes/prostate. We all assumed prostate cancer. It wasn’t until the results of the autopsy revealed Blasto.

I have heard it said Blasto affects only dogs with weakened immune systems. Luke was never sick a day in his life prior to this. It is possible his immune system became compromised from the stress of several bitches in heat and the extremely high temperatures. Luke was a very healthy dog in the prime of his life dying 2-weeks shy of his 8th birthday. He was not a digger or forager. When hunting, he covered ground quickly with a high head. We do live within sight of a stream, and even though the dogs have never been near the stream, we are well within a distance that the fungus can be present in the soil. We had not been around any areas of recent “excavation.” We do have young dogs that love to dig in the yard. The property right next to the barn, where the kennels are housed, is farmed. Did the plowing, raking, etc., kick up dust and Luke just happened to inhale the spore when the perfect conditions were present to release it? Or was it any of the hundreds of places all over the UP he had hunted the previous fall/winter? Maybe. We will never know where he happened along at the precise right time and right conditions.

There are theories that humans and dogs inhale the spores, but the disease never takes hold or that the fungus can lay dormant until a time of stress that compromises the immune system.

Luke did not present with the most likely symptoms of Blasto. I knew absolutely nothing about Blasto prior to Luke’s death and had only heard of it once–and coincidentally just a few months prior to Luke’s death. At first, I wanted to move and never hunt in the immediate area. Strangely, if you look at the map above of the “endemic areas,” it shows our area in PA as being a hot spot and not the UP. As it turns out, we’ve hunted for decades in areas endemic for Blasto and never knew anything about it. After all the research, I realize Blasto is still relatively rare and the conditions have to be “perfect” for the spores to release. Now, being acutely aware of all the symptoms, I am ever on alert for any changes or strange behavior in the dogs. The key is to know your dogs, know the symptoms of Blasto, and be diligent in getting your dog to the vet at the earliest indications. Your veterinarian may not know about Blastomycosis, so be prepared to enlighten him or her. Insist on testing either via a chest x-ray (although, remember that Luke’s lungs were clear and that I have a fantastic veterinarian with a lot of experience in Blasto cases), blood, urine, and/or tissue samples. Although, I should make something very clear. Luke really only acted depressed some days and was normal other days. He would not eat for two days, then he would eat. He was up and down. Just when I was convinced something was wrong, he would have a great day. After much discussion and contemplation, I started him on antibiotics when there was a tiny bit of discharge from his eye and a fever. I wrote in the kennel journal on the 4th of July, “Spent the night in the barn with the dogs, watching fireworks out the back door. Luke would sit with me for a bit, then go in his box. So strange. He did eat a little this morning. Eye booger and a fever of 103°F? Started him on antibiotics. Has to be Lymes or Anaplasmosis-not eating, losing weight, acts a bit sore but I can’t tell where… squatted to pee instead of lifting his leg….” He initially responded positively, but took a very fast downhill turn. We were at the veterinarian’s office July 9th. He died July 11th in my arms on the sofa at home. Luke was already too far gone and it happened fast. Knowing what I know now, and if I ever have another dog showing any of the symptoms, I will make sure every possible form of test was done and conclusively negative before considering other causes. Blastomycosis is only treatable if diagnosed early. Rule it out first.

I hope this helps educate more dog owners of the symptoms of Blastomycosis. I also hope it quells some of the myths surrounding the disease.

Please feel free to share your experiences as well as ask questions in the comment area below.

References:

Guant, M. Casey, DVM, and Susan M. Taylor, DVM, DACVIM. “Canine Blastomycosis: A Review and Update on Diagnosis and Treatment.” Veterinary Medicine (2009): n. pag. 1 May 2009. Web. 28 July 2012.

Resources:

- Blastomycosis in dogs: A fifteen-year survey in a very highly endemic area near Eagle River, Wisconsin, USA

- http://download.journals.elsevierhealth.com/pdfs/journals/1080-6032/PIIS1080603297709657.pdf

- A forum about Pet and Human Blastomycosis

- http://www.canineblastomycosis.com

- Research Updates: Antigen and antibody tests for diagnosing and monitoring blastomycosis in dogs

- Canine blastomycosis: A review and update on diagnosis and treatment

- Images of canine blastomycosis

- http://www.health.state.mn.us/divs/idepc/diseases/blastomycosis/basics.html

Hug your Llewellin Setter tonight… because you can!

-LML

You must be logged in to post a comment.